death and the maiden

franz schubert | wynton marsalis | caroline shaw

Friday, May 31 7:00pm

featuring guest violinist Mathea Goh

Schubert + Marsalis:

Gustav Klimt: Death and Life (1915)

Friday, June 14 7:00pm

featuring guest violinist Rosie Weiss

Schubert + Shaw:

First Presbyterian Church: Boise

950 West State Street, Boise Idaho

free

and open to the public

learn more about the music

-

(1797-1828)

String Quartet No. 14 in D minor, D. 810 Death and the Maiden

“The Maiden:

Pass me by! Oh, pass me by!

Go, fierce man of bones!

I am still young! Go, dear,

And do not touch me.

And do not touch me.

Death:

Give me your hand, you beautiful and tender creature!

I am a friend, and come not to punish.

Be of good cheer! I am not fierce,

Softly shall you sleep in my arms!”

—Matthias Claudius, 1774

Franz Schubert’s much-too-short life was filled with music from beginning to end. Instructed in the basics of music by both his father and his older brother Ignaz, Schubert played piano, violin, and organ, and also sang from the time he was very young.

By the 1820s Schubert was making some money from his compositions and was also part of a close-knit circle of artists and students who gathered regularly for “Schubertiaden.” However, starting in 1823, Schubert suffered from a number of hardships, most difficult of which was the illness (likely syphilis) that struck the young composer at the end of 1822. Despite this, Schubert’s music never stopped, and in fact progressed greatly as he grew sicker. (Program Notes by Jessie Rothwell)

Schubert was a poet of unfulfillable longing, of human vulnerability, of the excruciating sweetness of the yearning to be at peace. He famously said of himself:

“I feel myself to be the most unfortunate, the most miserable being in the world. Think of a man whose health will never be right again, and who from despair over the fact makes it worse instead of better, think of a man, I say, whose splendid hopes have come to naught, to whom the happiness of love and friendship offers nothing but acutest pain, whose enthusiasm (at least, the inspiring kind) for the Beautiful threatens to disappear, and ask yourself whether he isn’t a miserable, unfortunate fellow.”

“My peace is gone, my heart is heavy, I find it never, nevermore…”

In few other composer’s work do we find such stark and shattering juxtaposition of the human and the inhuman. Stony, unforgiving musical elements with no sense of malleability demand to be acknowledged, setting up a drama of the vulnerable individual in the clutches of destiny.

Schubert’s celebrated lyricism has at its core the suffering of recognizing that which can not be had. The most tender passages very often have a quality of distance, of a vision of that most dearly hoped for and yet felt to be ungraspable. For the qualities of splendid hopes, of the happiness of love and friendship, of enthusiasm for the Beautiful which Schubert mentions are far from absent from his work. But they appear only in the guise of dreams, representing a wounding optimism (Program Note by Mark Steinberg).

String Quartet No. 14, “Death and the Maiden,” is one of the pillars of the chamber music repertoire. Writing in 1824, Schubert did what many great composers do: he borrowed from himself. The quartet is titled for the second movement’s theme, taken from the song “Der Tod und das Mädchen,” written seven years earlier. The theme runs all the way through the quartet.

The first movement, an Allegro, sets the stage with typical major-minor instability and explosive outbursts. After a somber, chorale-like beginning to the Andante con moto, variations appear, using the “Death and the Maiden” accompaniment to dramatic effect. In the third movement, a Scherzo, the quartet is split into a high and low call-and-response, while a heavy dotted rhythmic figure dominates. The Trio that interrupts the movement is a breath of warm air that blows in and then dissipates as the Scherzo’s dark waltz returns.

The finale is a raging rondo that keeps the dotted rhythm from the Scherzo movement as it turns around and around in a traditional dance form called the tarantella. Schubert’s brilliant lyricism stands out even in the frantic movement – there are brief moments of respite within the fray where we hear longing sighs and reflective thoughts. The tarantella was traditionally thought to be a dance to ward off madness and death and at this late point in the composer’s life he was certainly grappling with these big themes – death, spirituality, inner struggle. The finale ends after breakneck runs and two short chords. The “Death and the Maiden” Quartet was first played in 1826 in a private home and wasn’t published until 1831, three years after Schubert’s death.

- Program Notes by Jessie Rothwell

-

(b. 1961)

String Quartet No. 1: At the Octoroon Balls (1995)

VII. Rampart St. Row House Rag

Wynton Marsalis is a musician of uncommon versatility, whose career is marked equally by excellence in classical music and in jazz. He received early exposure to both in the New Orleans milieu of his upbringing: the jazz he absorbed from his father, the distinguished pianist Ellis Marsalis; the classical came from school. Before graduating, he appeared twice as a soloist with the New Orleans Philharmonic, performing Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto and Bach’s second Brandenburg Concerto. Marsalis initially pursued a classical career at Juilliard, but was drawn back toward jazz during the summer of 1980, which he spent on tour with Art Blakey and his band. Yet perhaps elements of his classical training are reflected in his traditionalist ideals regarding jazz — most notably his staunch (controversial) opposition to the electronic instruments and rock elements introduced by musicians like Miles Davis during the 1970s and 80s, and his initiatives to promote jazz in traditional concert settings, including as founder and director of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City.

While Marsalis made his greatest fame in the world of jazz, he has continued achieving distinctions in classical music. He was the first individual to receive Grammy awards in jazz and classical categories in the same year (1984, for his jazz album Think of One and his recordings of trumpet concertos by Haydn, Hummel, and Leopold Mozart). His compositional output encapsulates these two inheritances, as exemplified in his “Blues Symphony,” with which he sought to prove that the “symphonic orchestra can and will swing.”

“At the Octoroon Balls,” Marsalis’s first string quartet, was commissioned jointly by Jazz at Lincoln Center and the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. The work draws on the composer’s view of life in New Orleans. As Marsalis put it: “A ball is a ritual and a dance. Everybody was in their finest clothing. At the Octoroon Balls there was an interesting cross-section of life. People from different stratums of society came together in pursuit of pleasure and fulfillment. The music brought people together.”

Program note by Peter Asimov

-

Blueprint (2016) written for the Aizuri Quartet

The Aizuri Quartet's name comes from "aizuri-e," a style of Japanese woodblock printing that primarily uses a blue ink. In the 1820s, artists in Japan began to import a particular blue pigment known as "Prussian blue," which was first synthesized by German paint producers in the early 18th century and later modified by others as an alternative to indigo. The story of aizuri-e is one of innovation, migration, transformation, craft, and beauty. Blueprint, composed for the incredible Aizuri Quartet, takes its title from this beautiful blue woodblock printing tradition as well as from that familiar standard architectural representation of a proposed structure: the blueprint. This piece began its life as a harmonic reduction — a kind of floor plan — of Beethoven's string quartet Op. 18 No. 6. As a violinist and violist, I have played this piece many times, in performance and in joyous late-night reading sessions with musician friends. (One such memorable session included Aizuri's marvelous cellist, Karen Ouzounian.) Chamber music is ultimately about conversation without words. We talk to each other with our dynamics and articulations, and we try to give voice to the composers whose music has inspired us to gather in the same room and play music. Blueprint is also a conversation — with Beethoven, with Haydn (his teacher and the "father" of the string quartet), and with the joys and malinconia of his Op. 18 No. 6.

Program note by Caroline Shaw

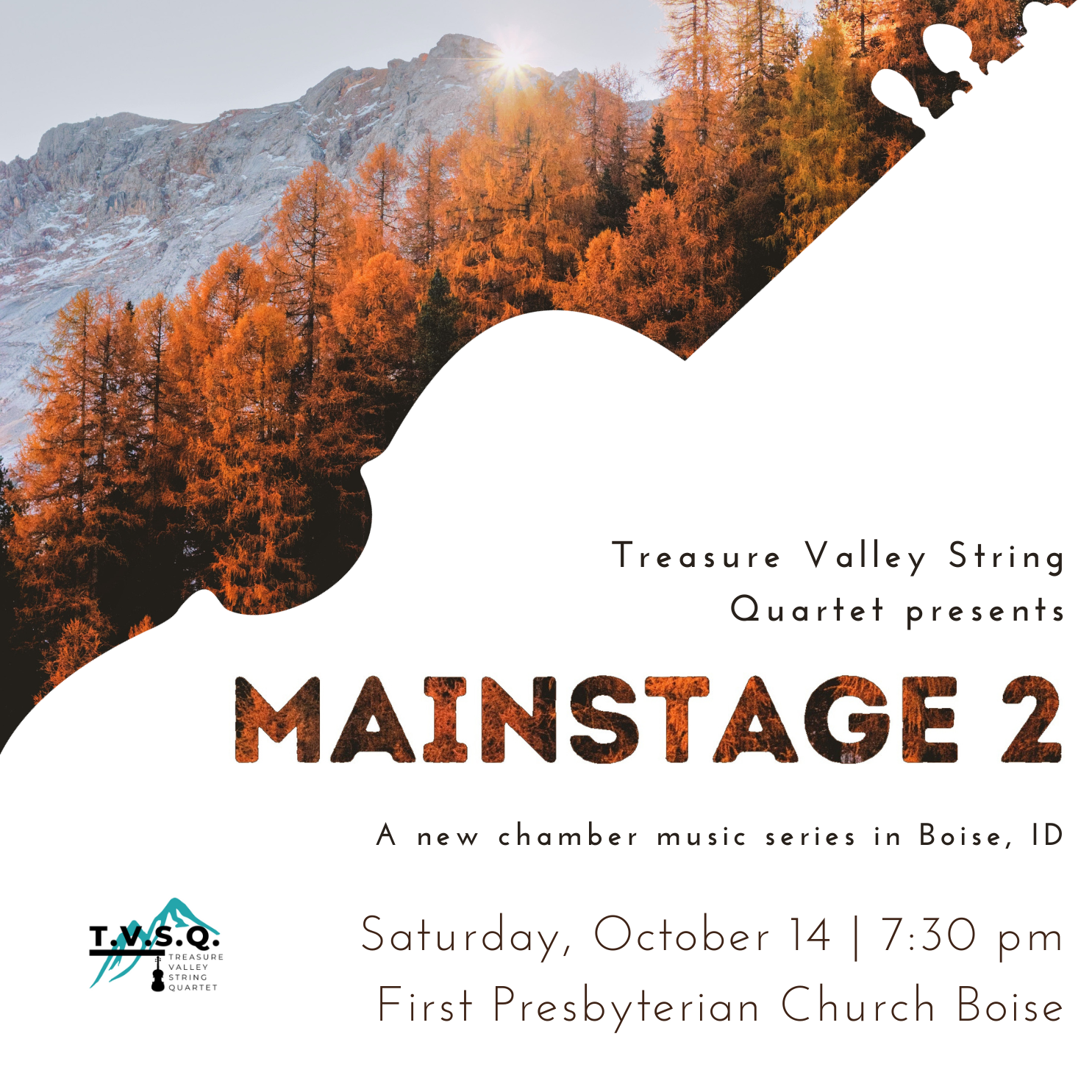

MainStage Series

A new chamber music series for the Treasure Valley.

Aug 2023 - January 2024